When I was in high school we decided to walk to Ottawa. By we I mean 6 of us who were all in the school’s camping club, which was called Outward Bound and modeled after the Colorado-based program with the same name. We camped year-round, regardless of the season or the weather. One year a teacher drove us up north of Kingston, Ontario, my hometown, for a winter camping weekend with the windows down in her car to “acclimatize” us. It was close to zero outside. By the time we got to our destination, a frozen lake 30 miles north, we were thoroughly “acclimatized,” which is to say: half frozen.

Every June, we traveled to Algonquin Park for a 7 day canoe trip. Unfortunately, June happens to be the time of the year when there’s an overlap between blackfly season and mosquito season. Sometimes the air was literally black with swarms of bloodthirsty insects.

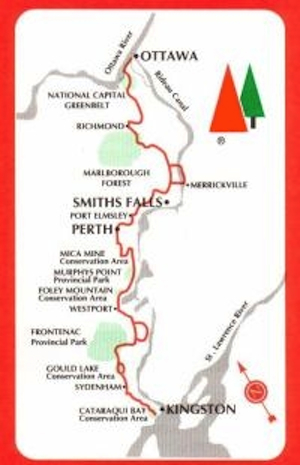

The year we decided to walk to Ottawa was the first year the Rideau Trail, a hiking trail between Kingston and Ottawa, opened. Ottawa is about 100 miles north but the trail is closer to 170 miles long.

A few weeks before spring break, we met in the school library and started to plan our expedition. We got maps of the trail and identified locations where we would camp at night based on how many miles we assumed we could walk each day. We had just enough time to make it over the break: 10 days from Friday to Sunday. We wrote lists for food and equipment. We arranged for a friend to drop off supplies halfway there. Another friend, who had his pilot’s license, said he would pick us up in Ottawa and fly us home if we made it. We knew he didn’t expect us to get there.

A few weeks before spring break, we met in the school library and started to plan our expedition. We got maps of the trail and identified locations where we would camp at night based on how many miles we assumed we could walk each day. We had just enough time to make it over the break: 10 days from Friday to Sunday. We wrote lists for food and equipment. We arranged for a friend to drop off supplies halfway there. Another friend, who had his pilot’s license, said he would pick us up in Ottawa and fly us home if we made it. We knew he didn’t expect us to get there.

The weather was cold–even for Ontario in April–on the day we started. A few friends and family saw us off at the start of the trail. We set off, brimming with optimism and good humor, our backpacks heavy with food and equipment. We crossed the 401–the major highway between Toronto and Montreal–a few hours later and it felt like we were leaving civilization behind. Soon after, we lost the trail in a muddy field. We consulted our maps and circled back to find it. We ended up at a dead end in a field covered in snow and ice.

We followed a county road that ran parallel to the trail and tried to rejoin it a mile or so later. Same result: impassable mud, snow and ice. I think I mentioned: spring was late that year. As darkess fell, we set up camp within view of a lonely farmhouse. Late that night it started to rain. It was cold; the temperature was in the mid 30’s. The next morning we relit our sodden campfire and and ate a miserable breakfast in a steady downpour. This was not what the way we’d imagined it. After breakfast, one member of the group deserted and headed toward the farmhouse to call for a ride home.

We walked all day in the pouring rain as frigid water soaked through our hats, our jackets, our pants, our socks and shoes. Piers, a stocky giant, had borrowed his dad’s hiking boots. Turns out they hadn’t been used in years, possibly even decades, and the stiff leather chaffed his feet and ankles, causing severe blisters. It was only Day 2. We tried to joke about our naiveté as we’d planned the trip in the warm library.

That night we reached Gould Lake, which was in a conservation area where we’d hiked and camped many times. At the south end of the lake was a barn used by the conservation society. But the barn was locked. Someone remembered hearing about a hidden key. We found it and got inside. The barn had no electricity but it had large propane heaters. We turned them on, emptied our backpacks and dried our drenched clothes and gear. We cooked hot food on a portable camp stove. We laid out our sleeping bags on the cold concrete floor, grateful for the shelter. We could hear the rain hammering on the tin roof. The next morning we ate breakfast and repacked our backpacks knowing that we would have quit if we hadn’t been able to stay dry that night.

Outside we discovered that the rain had turned to snow overnight but the sky was clearing. We followed the trail for a while but lost it in an area of steep hills and swampy ravines and had to use a compass to guide us across the rough terrain. After a couple of hours of strenuous bushwhacking, we found ourselves on a promontory overlooking the frozen lake. To our left, the shoreline curved around a wide bay–several miles of ravines and dense bush. Across from us we saw a small dock about half a mile across the ice. Our map showed us that the dock was close to the trail. A discussion ensued. Violent disagreements about what to do: weighing the risks of crossing the ice versus bushwhacking for several hours. We put it to a vote: the majority was for crossing the ice. We each grabbed a long branch to use as a pole in case we fell through. The sullen minority of dissenters followed reluctantly as we stepped onto the ice. We spread out to distribute our weight and headed for the dock, hearts pounding. The ice was slushy in places and dark colored. The water below would be freezing cold–enough to kill you in a few minutes. We walked as fast as we dared and the dock loomed closer. But, as we approached the shore, we saw there was open water in front of the dock. It was probably only a couple of feet wide but it looked like ten. Turning back was not an option. One by one we took a running leap over the water and onto the dock.

Outside we discovered that the rain had turned to snow overnight but the sky was clearing. We followed the trail for a while but lost it in an area of steep hills and swampy ravines and had to use a compass to guide us across the rough terrain. After a couple of hours of strenuous bushwhacking, we found ourselves on a promontory overlooking the frozen lake. To our left, the shoreline curved around a wide bay–several miles of ravines and dense bush. Across from us we saw a small dock about half a mile across the ice. Our map showed us that the dock was close to the trail. A discussion ensued. Violent disagreements about what to do: weighing the risks of crossing the ice versus bushwhacking for several hours. We put it to a vote: the majority was for crossing the ice. We each grabbed a long branch to use as a pole in case we fell through. The sullen minority of dissenters followed reluctantly as we stepped onto the ice. We spread out to distribute our weight and headed for the dock, hearts pounding. The ice was slushy in places and dark colored. The water below would be freezing cold–enough to kill you in a few minutes. We walked as fast as we dared and the dock loomed closer. But, as we approached the shore, we saw there was open water in front of the dock. It was probably only a couple of feet wide but it looked like ten. Turning back was not an option. One by one we took a running leap over the water and onto the dock.

I still look back on that as one of the riskiest things I’ve ever done in my life. It was a calculated risk but it could have ended very badly.

Why tell that story now so many years later? Because, as the founder of a startup, it seems totally familiar.

I conceived of Gigmor, my musician-matching website, in the warm library of my imagination and am now in the thick of all the usual, well-documented challenges facing unfunded startups: attracting and retaining real customers, building a team of people who believe in our mission, pitching investors, working on long overdue enhancements to the site, finding a path to profitability… Yup, it’s damn hard. It’s a roller coaster of emotion: from conquer-the-world-highs to 3 am panic attacks. But my years in the outdoors prepared me for this. You have to be able to talk yourself through the tough times, you have to pace yourself for a marathon, you have to deal with unexpected challenges. You have to ignore those who tell you you’re crazy, your idea sucks, you’ll never succeed. It’s like crossing that ice: failure is not an option. (And you need some luck too.) You have to keep going no matter how insurmountable the obstacles look. You have to have a lot of passion–enough to carry you through the tough times. Otherwise, the rational part of your brain that told you to quit a year ago would win the argument.

So back to the hike. Did we make it to Ottawa? The rest of that week is a blur. I remember our friend bringing us supplies of fresh food. He got out of his car and laughed at us. We must have looked pretty rough. I remember cold nights, interminable days of walking, Piers yelling, “Every step is pain!” But once we were past the potentially fatal danger of crossing that ice, everything else seemed possible. All we had to do was keep walking. Step by step, hour after hour, day after day.

So yes we made it. Our friend flew up to take us home. (He became a commercial pilot.)

Will Gigmor make it across the precarious spring ice and become the successful company I’m imagining? Damn straight. I’m betting on it.

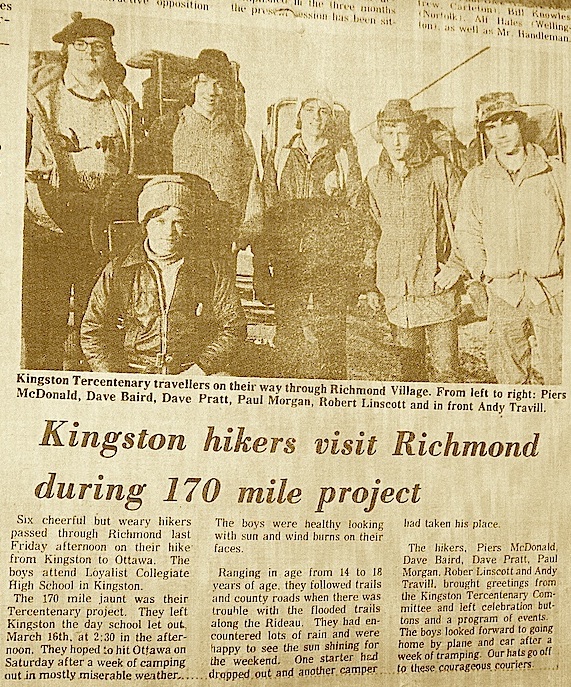

Here’s a picture of us with the full article in the Richmond Review, March 29, 1973.